The United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union has thrown global markets into turmoil in recent days. Given the result was the opposite of market expectations, the knee-jerk response was understandable, though likely overstated Brexit’s global (and hence Australian) impact. That said, Brexit is potentially devastating for the UK over the near-term, and to the European Union over the longer-term. What’s more, the Brexit shock comes at a vulnerable time for global markets, given sluggish earnings growth and elevated equity market valuations.

Panic selling overstates Brexit’s global impact

The magnitude of the global market sell-off in the wake of the Brexit decision likely overstates Brexit’s near-term importance for the global economy. After all, while the UK is the fifth largest economy in the world, it still accounts for only 2.5% of global GDP, while exports to the EU account for 3% of EU GDP.

And nothing changes in terms of the UK’s relations with the EU until it formally invokes Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, after which it has two years to negotiate an exit – or otherwise default to the trading status that other non-EU members share with the EU under World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules, which still imply relatively low tariff barriers.

The market reaction reflected traders being completely wrong-footed by the decision. Note just as global markets started to focus on the looming Brexit vote over the past few weeks, they were increasingly reassured by bookmakers that the odds of a “Leave” vote were quite low at only around 20%. Such complacency was evident in financial markets. The British Pound, for example, rose 4.6% against the US dollar in the five days prior to the vote – after which it slumped 8% when the poll results were clear.

Unlike during the 2008 financial crisis, the Brexit decision does not appear to place any systemic risks on the global banking sector – as the UK does not have massive foreign debts that need to be immediately repaid. What’s more, while the Brexit decision could increase the odds of other EU member states agitating for their own “exit” vote, it could also arguably induce the opposite effect if the UK economy quickly slips into a wrenching recession – as seems quite likely.

That said, the Brexit decision comes at a vulnerable time for the global economy – as the rally in risk markets since mid-February has come despite continued sluggish global growth, and has pushed equity market price-to-earnings valuations to relatively elevated levels. Should tensions in Europe rise, sending safe-havens such as the US dollar higher (along with gold and the Japanese yen), it could further weaken commodity prices and pressure emerging market economies.

Against this, global central banks stand ready to provide ample liquidity if required. The upshot of the Brexit decision is that the Bank of England, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan (due to safe-haven yen strength) are all likely to ease monetary policy further in coming months, and the Federal Reserve will likely postpone raising interest rates again for at least several more months.

The UK economy faces massive near-term uncertainty

Although the UK has two years to negotiate its exit from the EU, this will still leave UK corporates highly uncertain about their likely access to the key EU market within only a few years. The EU – and countries with free-trade agreements with the EU – account for around 60% of UK exports, and one fifth of UK GDP. The EU also accounts for around half of foreign direct investment into the UK, and one half of net-migration.

Accordingly, the biggest near-term costs will be a likely major hit to UK business sentiment, and associated hiring and investment decisions. Indeed, while non-EU members Norway and Switzerland managed to negotiate extensive EU market access, the UK seems less likely to be willing to continue contributing to the EU Budget, comply with EU regulations, and allow the free movement of labour.

At the other extreme, if no agreement is reached after two years, the EU’s treatment of the UK would eventually default to that shared with other non-EU members under World Trade Organisation rules. But while the EU imposes a relatively small average tariff of only 1.5% on non-EU products, tariffs on important UK sectors such as car production and food and alcohol manufactured products are notably higher. And WTO rules don’t cover administrative non-tariff barriers to trade, and are less comprehensive in the services sector – specifically this option could still seriously undermine London’s ability (under “passporting” rights) to operate as a European financial hub unless a specific sectoral agreement was put in place.

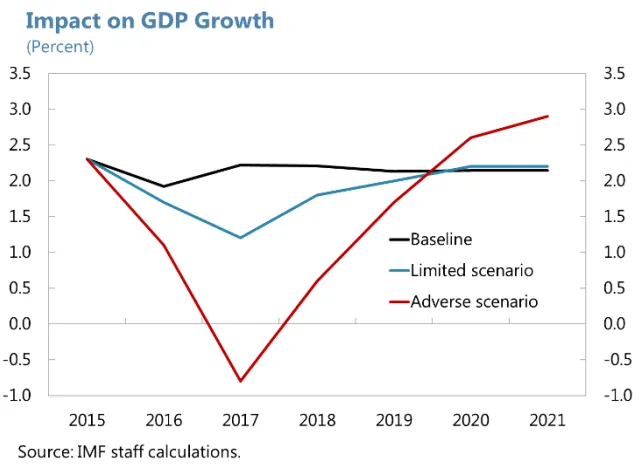

Estimates vary, but IMF estimates suggest UK growth could drop to 1.4% in 2017 (from around 2% in recent years) if continued high market access to the EU is speedily agreed. But GDP could contract by 0.8% if negotiations are protracted and the WTO “default” options seems likely. By way of comparison, during the financial crisis, the UK economy contracted by 0.5% and 4.5% in 2008 and 2009.

Direct impact on Australia should be limited

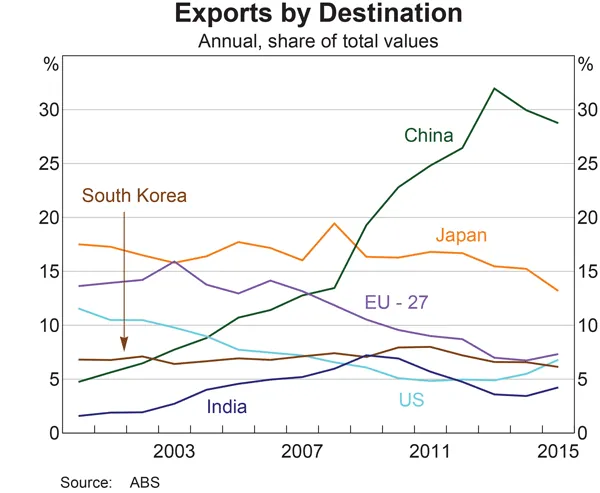

Australia’s direct trade and investment links with the UK have diminished over recent decades. In 2014-15, the UK accounted for only 2.2% of the nominal value of Australian exports. Of that, around one fifth was accounted for by tourism, and a further 10% by financial services. The main economic impact therefore might come from reduced UK tourism, particularly given the weakness in the British pound and likely slump in the UK economy.

At the margin, investment flows might also be affected. According to Austrade estimates, the UK accounted for 10% of the $735b stock of foreign direct investment in Australia at end-2015, the 3rd largest holding behind the United States and Japan. The UK’s share of FDI, however has been declining for some time.

All up, given limited trade and investment links, the main impact of the Brexit decision on the Australian economy will likely come through any spill over effects it has on global financial markets and business confidence. In this regard, although the Brexit decision alone should not unduly affect global financial markets, it is yet another negative factor that could cumulatively weigh on sentiment over the months ahead, and suggests a cautious stance with regards to risk assets might be warranted.

David Bassanese is the Chief Economist for BetaShares. BetaShares is an Australian manager of funds which are traded on the Australian Securities Exchange. BetaShares offers a range of exchange traded funds which cover Australian and international equities, cash, currencies, commodities and alternative strategies. Author website: www.betashares.com.au/insights/author/david-bassanese

This post was originally published at the BetaShares Blog at www.betasharesblog.com.au/brexit-implications-for-australian-investors