At this time of the year many investors and their advisers are focused on ensuring they implement the most tax efficient strategies in order to take advantage of any benefits or deductions before the end of the financial year. This post details an important but often underappreciated benefit that exchange traded funds (ETFs) can offer investors – tax efficiency. Tax-efficiency is, perhaps, a less visible benefit for investors, as, in the Australian financial market, fund manager performance is more often assessed on pre-tax returns, meaning investors may not be fully appreciative of this ETF related benefit.

Due to their typically low portfolio turnover, ETFs can potentially provide significantly better after-tax returns relative to that of a high turnover actively managed fund, assuming all other factors that affect returns are equal. Indeed, for broad Australian equities exposure, we provide an illustration of how an ETF can potentially improve after-tax returns up 1% p.a.

Another tax efficiency associated with ETFs involves their unique structure, which typically better insulates investors from having to pay capital gains tax if there is a high level of redemptions from other investors, when compared to traditional managed funds.

WHY LOW TURNOVER LOWERS TAX

One of the features of index-linked strategies, like those of ETFs, is that they usually don’t require a high turnover of stocks from year to year. The BetaShares FTSE RAFI Australia 200 ETF (ASX: QOZ), for example, had portfolio turnover of only around 10% over the past 12 months. By contrast, a study by Towers Watson estimated that the typical portfolio turnover for an Australian actively managed equity fund can be as high as 80% (Source: Towers Watson Tax Effective Investing Report 2011) .

Portfolio turnover can have important tax consequences. For starters, the lower the portfolio turnover of a managed investment, the fewer assets will be sold each year and therefore the lower the potential annual capital gains tax (CGT) bill investors face. Effectively, low turnover means the tax payable on any accruing capital gains in a portfolio will largely be deferred until the gains are realised at a later date – typically when investors sell their investment – which, in turn, means an investor’s portfolio value can remain higher for longer so they can get more benefit from return compounding over time.

Secondly, low portfolio turnover also means that a greater portion of the assets sold by the fund manager are likely to have been held for more than a year, meaning investors are more likely to benefit from capital gains tax discounts applicable to long-term asset holdings. In Australia, individual investors are able to apply a 50% discount to capital gains tax (CGT) when selling assets held for longer than one year, while superannuation funds (including SMSFs) can apply a 33% discount.

We can demonstrate these tax effects using a simple numeric example – details of which are provided in the technical appendix below.

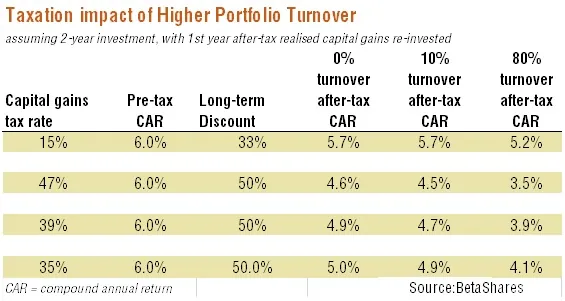

Assume, for example, that an investor places $100,000 in a managed investment that earns pre-tax capital growth of 6% p.a., and sells the fund after two years (ignoring management fees and costs and distributions). The table below considers three cases: 1) no turnover in the fund over the whole period; 2) a 10% turnover in the portfolio at the end of year one; and, 3) 80% turnover of the portfolio at the end of year one.

As seen in the table below, increasing portfolio turnover from 10% to 80% – assuming pre-tax returns are the same – significantly reduces post-tax returns. Indeed, for an investor in the top marginal income tax rate of 47% (including 2% Medicare levy), the post-tax annualised returns are reduced by a full percentage point, from 4.5% to 3.5%. For superannuation funds (including SMSFs), the post-tax annualised return is reduced by 0.5%.

Illustration only. Not indicative of any fund’s actual performance. Level of turnover can vary from fund to fund and year to year.

Also noteworthy, however, is the fact that small but positive turnover of only around 10% has a very marginal detrimental impact on returns (around 0.1%-0.2% p.a.) relative to the “buy and hold” case. Given that some asset turnover can be of benefit to investors – as it keeps a portfolio in line with the changes in market capitalisation or other relevant fundamental measures of a company’s size – the associated small detraction from after-tax returns relative to a “buy and hold” strategy may be a price worth paying for investors.

Indeed, indexing linked to some measure of a company’s size effectively means investors benefit from automatic survivorship bias – whereby companies doing badly and falling in size are eventually cut from the index and their portfolio, whereas companies succeeding in building their size are added to the index and their portfolio over time. Buy and hold investors need to remain vigilant, as they always face the risk of inaction if one of their stocks loses significant value over time.

DEALING WITH INVESTORS’ REDEMPTIONS

Another tax efficiency associated with ETFs is that their unique structure means investors are typically better insulated from having to pay capital gains tax if there is a high level of redemptions from other investors.

In the usual managed fund structure, large investor redemptions mean the fund manager has to sell underlying assets to meet the cash demands of departing investors. In most cases – and especially where there are many small investors selling at the same time – it is administratively complex for the fund manager to assign (or “stream”) the capital gains tax associated with these sales to the individual investors in question. Instead, the fund is left with the capital gains tax liability which in turn is passed on to remaining investors in the fund at the end of the financial year.

With an ETF however, even if many small investors seek to sell their ETF holdings on the ASX at the same time, it is the authorised participant (AP) who facilitates these sales (effectively buying ETF units from individual investors in return for cash), and who then undertakes the redemption process with the ETF provider. Due to the fewer but larger redemptions involved, it is easier for the ETF provider to “stream” the associated capital gains tax payable to the AP, sparing remaining investors in the ETF from having to pay this tax.

All up, along with low cost, transparency and diversification, tax efficiencies are an important benefit associated with ETFs that investors should keep in mind.

Note: BetaShares is not a tax adviser and this information should not be construed as tax advice. You should obtain professional, independent tax advice before making any investment decision.

Technical Appendix

If there is no turnover in the fund, the fund earns a compound 6% pre-tax return each year, growing to $112,360 on the date of sale. In turn, that means the investor is liable to pay tax on capital gains of $12,360. Assuming they are in the top marginal tax rate of 47%, and receive the 50% CGT discount, their tax payable is $2,905 (including Medicare levy), reducing the after-tax value of their investment to $109,455 – for an annualised two-year after-tax return of 4.6%. For a superannuation fund receiving a 33% discount on their 15% tax rate, the annualised two-year return is 5.7%.

With 80% portfolio turnover at the end of the first year, however, the investor is liable to pay CGT (without any discount) on the 80% value of shares sold at the end of year one – reducing the value of the portfolio heading into year 2 even if all after-tax returns are re-invested. What’s more, when the whole investment is then sold at the end of year 2, around 80% of the gains relate to newly purchased assets held for less than one year, and so are again not subject to a CGT discount. Only the 20% of the portfolio held for two years is eligible for the discount. The end result is that the annualised after-tax return for an investor in the top income tax bracket falls to 3.5%. For superannuation funds, the return falls to 5.2%.

With portfolio turnover of only 10% at the end of year one, however, the return for an investor in the top income tax bracket is 4.5% – or only 0.2% less than the “buy and hold” case of zero turnover. For super funds, the return remains very close to the 5.7% return for the zero turnover funds (the tax penalty associated with turnover is lower for super funds due to their lower marginal tax rate). The after-tax return is higher than in the case of 80% turnover because less CGT needs to be paid at the end of year one – allowing more of the portfolio to earn extra returns in year two – and because more of the CGT payable at the end of year two is subject to the CGT discount.

David Bassanese is the Chief Economist for BetaShares. BetaShares is an Australian manager of funds which are traded on the Australian Securities Exchange. BetaShares offers a range of exchange traded funds which cover Australian and international equities, cash, currencies, commodities and alternative strategies. Author website: www.betashares.com.au/insights/author/david-bassanese

This post was originally published at the BetaShares Blog at www.betasharesblog.com.au/etfs-after-tax-outcomes